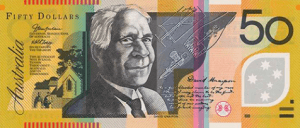

Australian currency is a curious mixture, with the coins dominated by the monarch and varieties of fauna, apart from the $2 coin, which has QEII on one side and Gwoya Tjungurrayi, an Aboriginal tribal elder, on the other. The notes exhibit a motley collection of Australian notables, some more well known than others (by me, anyway: BanjoPaterson, Edith Cowan, Nellie Melba, John Monash). Less well known are Mary Reibey on the $20 note (a rags-to-riches story of a girl transported to Australia as a 13-year-old convict) and the Aboriginal man depicted on the $50 note, David Unaipon.

Australian currency is a curious mixture, with the coins dominated by the monarch and varieties of fauna, apart from the $2 coin, which has QEII on one side and Gwoya Tjungurrayi, an Aboriginal tribal elder, on the other. The notes exhibit a motley collection of Australian notables, some more well known than others (by me, anyway: BanjoPaterson, Edith Cowan, Nellie Melba, John Monash). Less well known are Mary Reibey on the $20 note (a rags-to-riches story of a girl transported to Australia as a 13-year-old convict) and the Aboriginal man depicted on the $50 note, David Unaipon.

Another Tasmanian Aboriginal I should have known about – Fanny Cochrane Smith*, who made the only known recordings of an original indigenous language

I’ve gone through life knowing regrettably little about Australian history, and even less about indigenous history. What little history we studied was strongly British-focussed, and I could certainly name more American Indian historical figures (Pocahontas, Geronimo, Sitting Bull, Cochise, Crazy Horse, …) than I could name their Australian indigenous equivalents (Truganini and King Billy was about it – I’m Tasmanian). Over the years, my interaction with the original Australians has been sporadic, the most memorable being my chance meeting with my rugby hero, Mark Ella.

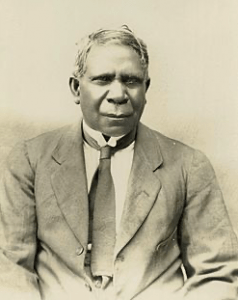

So I was curious about the life of David Unaipon, and an online search revealed a fascinating and impressive character. Born David Ngunaitponi in 1872 and lived till the grand old age of 94. He was one of a family of nine, and grew up and was educated at a mission in South Australia, showing early promise of things to come: “I only wish the majority of white boys were as bright, intelligent, well-instructed and well-mannered, as the little fellow I am now taking charge of.”

In his teenage years David moved to Adelaide to work as a servant, his employer C.B. Young recognising his potential and encouraging his interests in literature, philosophy, science and music. He was also deeply religious, later becoming a travelling Christian preacher, an activity he continued for decades, at the same time perceiving close links between Christianity and Aboriginal culture. As he was obsessed with correct English and spoke in archaic classical English, he must have been a captivating orator.

His interest in science was mostly focussed on physics, and he became expert in ballistics, though a main lifelong passion became inventions. David is credited with specifying details of how to convert rotary motion into tangential reciprocating movement, one application being for sheep shears. Overall he took our provisional patents for 19 inventions, and even before WW1 came up with a design for a helicopter based on the aerodynamics of the boomerang. Right into old age he indulged in the fruitless search for a perpetual motion machine.

As he grew older, David Unaipon also increasingly became a writer, orator and activist, using his speaking skills to advance the cause of his people. Though often refused accommodation and/or sustenance, he travelled widely and spoke boldly on Aboriginal rights and culture. Though he probably wouldn’t be considered a radical (he was opposed to the ‘Day of Mourning’ at the 150th anniversary of the First Fleet), he fought for recognition, championing self-determination and being arrested for attempting to provide a separate territory for Aboriginals in central and northern Australia.

As he grew older, David Unaipon also increasingly became a writer, orator and activist, using his speaking skills to advance the cause of his people. Though often refused accommodation and/or sustenance, he travelled widely and spoke boldly on Aboriginal rights and culture. Though he probably wouldn’t be considered a radical (he was opposed to the ‘Day of Mourning’ at the 150th anniversary of the First Fleet), he fought for recognition, championing self-determination and being arrested for attempting to provide a separate territory for Aboriginals in central and northern Australia.

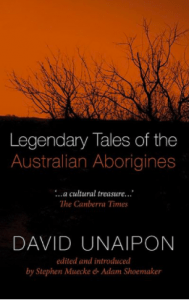

His activism was buttressed by his voluminous and proficient writing for a variety of sources, including newspapers. David Unaipon was the first published Aboriginal writer, a major work being Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines. The background to the book is instructive, as explained by the latest publishers:

His activism was buttressed by his voluminous and proficient writing for a variety of sources, including newspapers. David Unaipon was the first published Aboriginal writer, a major work being Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines. The background to the book is instructive, as explained by the latest publishers:

In the 1920s, under contract to the University of Adelaide, he was commissioned to collect traditional Aboriginal stories from around South Australia. He also acted as a ‘collector’ for the Aborigines Friends’ Association. Most of the stories come from his own Ngarrindjeri people, but some are from other South Australian peoples.

The stories were published in 1930 as Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals, but the author of the work was given as W. Ramsay Smith, FRS, anthropologist and Chief Medical Officer of South Australia. Unaipon’s name does not appear anywhere in the book, except where he is mentioned in passing as a ‘narrator’.

That wrong at least has now been righted.

* The surname Smith reminded me that when I was doing maths at the University Tasmania, there was a fellow student, Graeme Smith, who I recall was of indigenous heritage. In our Honours group he was the best mathematician by far – didn’t bother to go to lectures until threatened by Prof Elliot that he wouldn’t get his degree unless he participated. He’d sit there looking uninterested and not taking notes, every now and then terrifying the tutor by asking difficult questions. I wonder if he was Fanny’s great (or great-great) grandson!