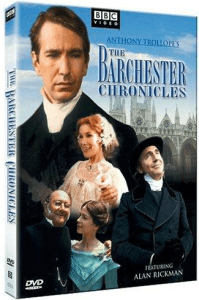

As I’ve previously written, I’m a fan of the author Anthony Trollope (1815 – 1882). His books are engaging, wry, and conjure up visions of life in the latter half of the nineteenth century. If you haven’t read any of his voluminous output, you’ll at least have heard of some of the films and series based on his work: The Barchester Chronicles, Doctor Thorne, The Pallisers, The Way We Live Now, …

As I’ve previously written, I’m a fan of the author Anthony Trollope (1815 – 1882). His books are engaging, wry, and conjure up visions of life in the latter half of the nineteenth century. If you haven’t read any of his voluminous output, you’ll at least have heard of some of the films and series based on his work: The Barchester Chronicles, Doctor Thorne, The Pallisers, The Way We Live Now, …

Although he spent a good deal of his life working at a seemingly pedestrian job at the Post Office, he also travelled extensively and wrote of his adventures. These non-fiction works include observations of his visits to Australia, to which one of his sons had emigrated.

‘Australia and New Zealand’, written in 1873, contains much insightful commentary, though Trollope does at times dwell too long on what might be called the political economy: laws relating to landowning and squatters, the relative wages and lives of rural workers, colonial power and politics, and so on. More interesting are the sections on the goldfields, travelling and the struggles of the developing colonial society.

To give you a taste of what’s to be found, here’s some quotes from Chapters 31 and 32, which focus on Victoria. At the time of his visit, the colony had been established for 40 years, and Trollope opens with the following:

I dislike the use of superlatives, especially when they are applied in eulogy; nevertheless, I feel myself bound to say that I doubt whether any country in the world has made quicker strides towards material comforts and well-being than have been effected by Victoria. She is not forty years old, all told … and she has already at her command most of the enjoyments of civilised life.

Trollope was particularly complimentary of the standard of newspapers in Australia, and drew special attention to the Argus. He was also mostly positive about the railway systems, though naturally commented on the lack of standardisation between the colonies, particularly Sydney and Melbourne. An accomplished horseman and frequent traveller on highways and byways, he was less impressed with the state of the roads:

The badness of the roads is, however, remarkable throughout Australia,—and it is equally remarkable that though the roads are very bad, and in some places cannot be said to exist, nevertheless coaches run and goods are carried about the country. A Victorian coach, with six or perhaps seven or eight horses, in the darkness of the night, making its way through a thickly timbered forest at the rate of nine miles an hour, with the horses frequently up to their bellies in mud, with the wheels running in and out of holes four or five feet deep, is a phenomenon which I should like to have shown to some of those very neat mail-coach drivers whom I used to know at home in the old days. I am sure that no description would make any one of them believe that such feats of driving were possible. I feel that nothing short of seeing it would have made me believe it.

The coaches, which are very heavy, and carry nine passengers inside, are built on an American system, and hang on immense leathern springs. The passengers inside are shaken ruthlessly, and are horribly soiled by mud and dirt. Two sit upon the box outside, and undergo lesser evils. By the courtesy shown to strangers in the colonies I always got the box, and found myself fairly comfortable as soon as I overcame the idea that I must infallibly be dashed against the next gum-tree. I made many such journeys, and never suffered any serious misfortune. I feel myself bound, however, to say that Victoria has not advanced in road-making as she has in other matters.

This chapter also includes observations on the indigenous population of Australia, and provide a number of insights. He calls the region he visited Gimps Land and, though it is certainly referring to what is now known as Gippsland, I’ve been unable to find any other reference to it by the name he uses. It may be just a misprint in the copy I’ve been reading, of course, though it does occur in multiple instances. Anyway, getting back to the point, although Trollope does at times use terms commonly associated with colonialists (e.g. reference to ‘savages’), a detailed reading reveals a more nuanced perspective, as revealed by the following quotes:

When in Gimps Land I visited an establishment called Ea ma Yuck [probably Ramahyuck], of a missionary character, maintained for the civilisation, christianisation, and general improvement of the black races.

It has been only natural, only human, that efforts should be made by the invading race to ameliorate the condition of these people, and,—to use the word most common in our mouths,—to civilise them. We have taken away their land, have destroyed their food, have made them subject to our laws which are antagonistic to their habits and traditions, have endeavoured to make them subject to our tastes, which they hate, have massacred them when they defended themselves and their possessions after their own fashion, and have taught them by hard warfare to acknowledge us to be their masters.

Gradually we have seen them disappearing before us,—sinking into the earth, as it were, as they made way for us. They have not retreated. Though personal property has been ignored, tribal property, the right of each tribe to its own territory, has been fully acknowledged among them,—so that to retreat was impossible. The only land to which they could have retreated was already occupied. As we have scattered ourselves onwards, these tribes have melted away. Their women have ceased to bear children, and their men have waxed prematurely old. Fragments of them only remain, and the fragments of them are growing still smaller and smaller. Within the haunts of white men, and under the tutelage of white men, they have learned to wear clothes, and to drink, and to be covetous of tobacco and money,— and sometimes to do a little work. But with their rags, and their pipes, and their broken English, they are less noble, less sensitive of duty, less capable of protracting life than they were in their savage but subdued condition.

All very dismal, but a reasonably fair summation, I think we’ll agree. But did he have anything to say on a positive note? Certainly, and this is apparent in his assessment of the children in the school.

We can teach them to sing psalms,—and can do so with less labour than is generally necessary for white pupils, and in better time. If we take the children early enough we can teach them to read and write,— and as I saw at Ea ma Yuck, can teach them to do so in a manner that would be thought very excellent among white children of the same age. The glib, pattering portions of our religious services are pleasant to them,—those portions in which we must be aware that there is always much of mere repetition among ourselves and our own children; for who can dare to say that as our hymns and chants are sung in church, it is the usual condition of the heart to be lifted up to the full meaning of the words?

I heard the children examined in the school, — about thirty I think there were,—and I was much struck by their proficiency. Their writing was peculiarly good, as was also their memory. They are a mimetic people, very quick at copying, and gifted with strong memories.

I may add that Mr. Hagenauer has gained the confidence of the black natives, not only of his own establishment, but of the surrounding districts generally, to a degree that, I think, has never before been reached. It has been the absence of this confidence which has created the almost internecine wars that have raged between the two races. But the more I liked the man, the more strongly I felt that the game was not worth the candle, and that I would fain hope that he might live to shine in some more useful sphere of labour.

Plenty there to reflect on, I’m sure you’ll agree. It also reveals Trollope’s religious leanings, which lean towards agnosticism. This may be a bit strong, though there is no doubt that he abhorred ecclesiastical arrogance.

On a lighter note, Trollope writes in detail about the Australian wine industry, well established by the time of his visit. And he doesn’t hold back!

Australia makes a great deal of wine,—so much and so cheaply that the traveller is surprised at finding how very little of it is used by the labouring classes. Among them some do not drink at all, some few drink daily,—and many never drink when at work, but indulge in horrible orgies during the few weeks, or perhaps days, of idleness which they allow themselves. But the liquor which they swallow is almost always spirits—and always spirits of the most abominable kind. They pay sixpence a glass for their poison, which is served to them in a cheating false-bottomed tumbler so contrived as to look half-full when it contains but little. The dram is swallowed without water, and the dose is repeated till the man be drunk.

The falseness of the glass seems to excuse itself, as the less the man has the better for him;—but the fraud serves no one but the publican, for though the “nobbler” be small,—a dram in Australia is always a nobbler,—there is no limit to the number of nobblers.

The concoction which is prepared for these poor fellows is, I think, even worse than that produced by the London publican. At home, however, beer is the wine of the country, and beer is the popular beverage at any rate with the workmen of this country. In all the Australian colonies, except Tasmania, wine is made plentifully,—and if it were the popular drink of the country, would be made so plentifully that it could suffice for the purpose. All fruits thrive there, but none with such fecundity as the grape. … The wine was certainly superior both in flavour and body to the ordinary wine drank by Parisians. … The best that I drank was in South Australia, but I did not much relish them. I thought them to be heady, having a taste of earth, and an after-flavour which was disagreeable. This may have been prejudice on my part. It may be that the requisite skill for wine making has not yet been attained in the colonies. Undoubtedly age is still wanting to the wines, which are consumed too quickly after the tinging. … France and Italy arc temperate because they produce a wine suitable to their climate. Australia, with a similar climate, produces wine with equal ease, and certainly,—I speak in reference to the common wine,—as good a quality.

There is now on sale in Melbourne, at the price of, I think, threepence a glass,—the glass containing about half a pint,—the best that I ever drank. It is a white wine made at Ye ring, a vineyard on the Upper Yarra, and is both wholesome and nutritive. Nevertheless, the workmen of Melbourne, when they drink, prefer to swallow the most horrible poison which the skill of man ever concocted.

Yes, Yering estate is a well-known and highly regarded Australian wine-maker, and its history dates back to the very early days of the colony, specifically in 1838.

Overall, Trollope’s travel tales make for fascinating reading, especially as it’s so close to home. I haven’t finished it yet, and there’s a chapter to come on my birthplace, Tasmania, so perhaps there’ll be another post on this marvellous writer.