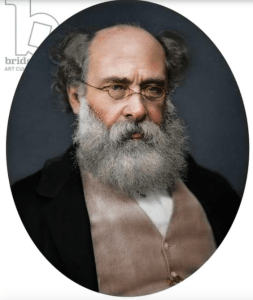

A bit strong? What is there to love, I hear you ask, about an author from the 1800s who spent most of his life as a civil servant in the Post Office, who got up at 4:30 each morning to pen a couple of thousand words before he went to work, and who wrote a book called The Three Clerks, which, as the title suggests, was about three men working for the Weights and Measures Office?

A bit strong? What is there to love, I hear you ask, about an author from the 1800s who spent most of his life as a civil servant in the Post Office, who got up at 4:30 each morning to pen a couple of thousand words before he went to work, and who wrote a book called The Three Clerks, which, as the title suggests, was about three men working for the Weights and Measures Office?

In my retirement I’ve taken to reading more than ever, and have delighted in delving into a variety of authors and their fiction and non-fiction. Some I’ve revisited from a longterm liking of their contributions (Philip Roth), while other have been recent discoveries (John Updike, Gary Disher). By that I don’t mean recent authors, as the majority come from my exploration of the classics, with titles gathered from opportunity shops and freebies on the Kindle. An example is George Orwell, whose complete works are easily obtainable. Most of his books are wonderful (Burmese Days, The Road to Wigan Pier, etc.), though I found 1984 to be my least favourite, being rather tedious in sections.

A little hesitating I started on The Three Clerks, but rapidly became entranced by Trollope’s style and storylines. First, Trollope has a way of drawing you right in to the story, through careful description of people and places, and an ability to provide fascinating insight into the societal mores of the time. If you want to know how the population of the Victorian era thought and acted, Trollope is supreme. An added dimension is the insertion of personal asides and comments, giving the text an appealingly whimsical flavour: “I think the greatest rogues are they who talk most of their honesty.”

A little hesitating I started on The Three Clerks, but rapidly became entranced by Trollope’s style and storylines. First, Trollope has a way of drawing you right in to the story, through careful description of people and places, and an ability to provide fascinating insight into the societal mores of the time. If you want to know how the population of the Victorian era thought and acted, Trollope is supreme. An added dimension is the insertion of personal asides and comments, giving the text an appealingly whimsical flavour: “I think the greatest rogues are they who talk most of their honesty.”

Having started, I was hooked and a few months ago downloaded The Complete Works of Anthony Trollope onto my Kindle. I’m now merrily making my way through the collection, interspersing it with contrasting books from the likes authors PJ O’Rourke and others. I’ve also been flipping between Trollope’s Framley Parsonage and his marvellous autobiography, appropriately titled Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.

Anthony Trollope’s life was infinitely more interesting (and challenging) than we might initially imagine. Though of what we would consider middle class society, he grew up in misery and poverty (his mother started writing at the age of 57, saving the family from destitution), suffering greatly until a work-related move from England to Ireland, where his life almost instantly turned around. He’d been employed by the Post Office for some time, and as no-one else wanted the Irish posting, he took a chance and took it up. It was the beginning of his happy life, though it was over a decade before his writing began to earn any appreciable income.

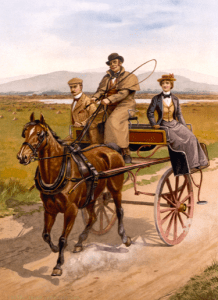

And his work was by no means office bound. One of his duties was to follow up individually with complainants, and here is his hilarious account of one such encounter:

A gentleman in county Cavan had complained bitterly of the injury done to him by some arrangements at the Post Office. The nature of his grievance has no present significance; but it was so unendurable that he had written many letters, couched in the strongest language. He was most irate, and indulged himself in that scorn which is easy to an angry mind. The place was not in my district, but I was borrowed, being young and strong, that I might remember the edge of his personal wrath. It was mid-winter, and I drove up to his house, a squire’s country seat, in the middle of a snowstorm, just as it was becoming dark.

A jaunting car

I was on an open jaunting car, and was on my way from one little town to another, the cause of his complaint having reference to some mail conveyance between the two. I was certainly very cold, and very wet, and very uncomfortable when I entered his house. I was admitted by a butler, but the gentleman himself hurried into the hall. I at once began to explain my business. “God bless me!” he said, “you are wet through. John, get Mr. Trollope some brandy and water – very hot.” I was beginning my story about the post again when he himself took off my great-coat, and suggested that I should go up to my bedroom before I troubled myself with business. “Bedroom!” I exclaimed. Then he assured me that he would not turn a dog out on such a night as that, and into a bedroom I was shown, having first drank the brandy and water standing at the drawing room fire. When I came down I was introduced to his daughter, and the three of us went into dinner. I shall never forget his righteous indignation when I again brought up the postal question on the departure of the young lady. Was I such a Goth as to contaminate wine with business? So I drank my wine, and then heard the young lady sing while her father slept in his armchair. I spent a very pleasant evening, but my host was too sleepy to hear anything about the Post Office that night. It was absolutely necessary that I should go away the next morning after breakfast, and I explained that the matter must be discussed then. He shook his head and wrung his hands in unmistakable disgust, – almost in despair. “But what am I to say in my report?”, I asked. “Anything you please,” he said. “Don’t spare me, if you want an excuse for yourself. Here I sit all day – with nothing to do; and I like writing letters.” I did report that Mr. ___ was now quite satisfied with the postal arrangement of his district; and I felt a soft regret that I should have robbed my friend of his occupation. Perhaps he was able to take up the Poor Law Board, or to attack the Excise. At the Post Office nothing more was heard from him.

So Trollope’s life in the Post Office was not as we might envisage. As he developed a reputation for the quality of his service, he was sent on overseas postings to improve the work of the Post Office in British dependencies and colonies (e.g. West Indies), leading to a series of non-fiction accounts of his travels. His penchant for travel extended into his later years, and included trips to the US, as well as time spent in Australia. I’m looking forward to reading his accounts of his time there (he even visited my city of birth, Hobart).

Another facet of Trollope’s writing is the (unsurprising) use of what were then common slang terms, typically of derision. I had a fair idea what a ‘lickspittle’ was, but needs to look up ‘tuft-hunter’ – turns out it’s someone that seeks association with persons of title or higher social status (especially in universities); that is, a snob. The tuft part seems to come from academic gowns, which traditionally had golden tassels or tufts (hence Tufts University).

Trollope wrote for money. He freely admitted it, and made powerful arguments justifying his stance. Unfortunately, for this he was somewhat reviled by some contemporaries and critics. Reading his autobiography makes his position even more understandable, given the supreme difficulties he faced with respect to money for much of his relay life. On a more pleasant note, he had a passion for riding, especially riding to hounds, though he admits to never quite getting the hang of the hunt. For him, it was the supreme pleasure of riding across fields and through woods, with an aversion to roads. As he revealingly writes,

The cause of my delight in the amusement I have never been able to analyse to my own satisfaction. In the first place, even now, I know very little about hunting, – though I know very much of the accessories of the field. I am too blind to see hounds turning, and cannot therefore tell whether the fox has gone this way or that. Indeed all the notice I take of hounds is not to ride over them. My eyes are so constituted that I can never see the nature of a fence. I either follow some one, or ride at it with the full conviction that I may be going into a horse-pond or a gravel-pit. I am very heavy, and have never ridden expensive horses. I am also now old for such work, being so stiff that I cannot get on to my horse without the aid of a block or a bank. But I ride still after the same fashion, with a boy’s energy, determined to get ahead if it may possibly be done, hating the roads, despising young men who ride them, and with a feeling that life can not, with all her riches, have given me anything better than when I have gone through a long run to the finish, keeping a place, not of glory, but of credit, among my juniors.

There’s more … and more to love. I’m certainly still on my Trollope journey, and I encourage you to take one with Trollope too.