An advantage of retirement is the time that becomes available for reading. I relish it, read regularly, and love discovering (largely) unknown titles. Most are discovered serendipitously; wandering among the shelves of bookshops (new and second-hand), visiting op-shops or meandering around markets. Particular examples include Lady Spy, Gentleman Explorer, which caught my eye simply because the biography’s fascinating subject was a Murphy, and Bad Faith, which tickled my fancy when I read on the blurb that an alcoholic Tasmanian, Myrtle Jones, was intimately connected with the worst Nazi collaborator of the French Vichy government in WW2. Other exciting reads include those that offer a fresh, and sometimes personal, perspective on well-known events and historical events. My favourite example is V2, an autobiographical account of the German rocket programme of WW2 by the German General responsible for its oversight, Walter Dornberger.

These books are relatively well-known. There are also many that are published (or self-published) in small numbers that remain unknown to the general reading public. We get to hear about them only by chance or through a friend associated with their publication. I have a few interesting instances.

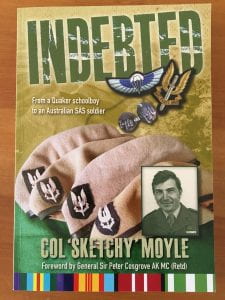

I was at school at the same time as a boy from Zeehan on the West coast of Tasmania, Colin Moyle. While trying to track down his brother for a rugby reunion, I learned that he’d published a book on his experiences as a soldier (unusual for someone who attended a pacifist Quaker school). His motivation was partly based on his reading of Sir Peter Cosgrove’s autobiography, which included reference to Colin during battle in the Vietnam War.

I was at school at the same time as a boy from Zeehan on the West coast of Tasmania, Colin Moyle. While trying to track down his brother for a rugby reunion, I learned that he’d published a book on his experiences as a soldier (unusual for someone who attended a pacifist Quaker school). His motivation was partly based on his reading of Sir Peter Cosgrove’s autobiography, which included reference to Colin during battle in the Vietnam War.

To add his personal perspective to the tale, Colin decided to write Indebted: From a Quaker schoolboy to an Australian SAS soldier. As Cosgrove himself wrote in the foreword to Indebted, “It is pithy and pungent, always insightful, often hilarious. Col’s love of family, the Army and Australia calls from its pages. It is a fascinating and compelling yarn.”

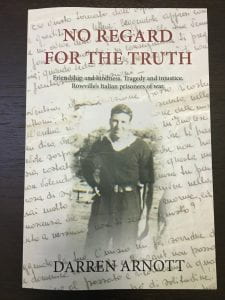

I came across the next book on my list through a friend whose Italian father had fought in WW2 and was captured and sent to Australia. Did you know that there were 18,000 Italian prisoners of war sent to Australia? I didn’t, and the book, No Regard for the Truth, is about one of them. It’s not a happy tale, as it tells the tragic story of Rodolfo Bartoli, who was shot dead by the the commandant of the Rowville internment camp in March 1946, when the war was well and truly over. The book’s title, No Regard for the Truth, is a quote from a judge, as he summarised his findings concerning the conduct of the commandant and his collaborators in the cover-up of the circumstances. As the summary explains, the book “follows the police investigation, Military Court of Inquiry, Coroner’s Inquest, Government inquiry and the subsequent court-martial hearings. Disturbing revelations about the camp administration begin to emerge – drunkenness, prisoner assaults, theft of property, the reckless firing of weapons and a desire to brush away the truth.”

I came across the next book on my list through a friend whose Italian father had fought in WW2 and was captured and sent to Australia. Did you know that there were 18,000 Italian prisoners of war sent to Australia? I didn’t, and the book, No Regard for the Truth, is about one of them. It’s not a happy tale, as it tells the tragic story of Rodolfo Bartoli, who was shot dead by the the commandant of the Rowville internment camp in March 1946, when the war was well and truly over. The book’s title, No Regard for the Truth, is a quote from a judge, as he summarised his findings concerning the conduct of the commandant and his collaborators in the cover-up of the circumstances. As the summary explains, the book “follows the police investigation, Military Court of Inquiry, Coroner’s Inquest, Government inquiry and the subsequent court-martial hearings. Disturbing revelations about the camp administration begin to emerge – drunkenness, prisoner assaults, theft of property, the reckless firing of weapons and a desire to brush away the truth.”

What made the tale especially poignant is that Rodolfo had become engaged to a local girl, the daughter of a farmer on whose property he had been working. The farmer approved of the relationship, which was also supported by Rodolfo’s family back in Italy. It’s an important contribution to an aspect of Australian history with which most of us are unfamiliar.

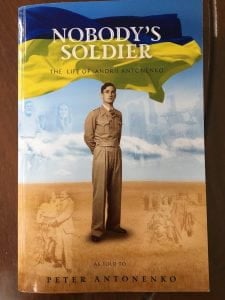

One of my neighbours, Peter Antonenko, has written a fascinating book about his father Andrii. To be strictly correct, the book is Andrii’s memoir of his life, as recounted to Peter. Nobody’s Soldier tells the harrowing tale of Andrii’s early life, as an exemplar of the horrors that Stalin’s Russia brought against the people of Ukraine. These horrors started for him in his early teens, and continued through years of unimaginable struggle and hardship. That he emerged as such an apparently calm, decent and loving person is a testament to his resilience and strength.

One of my neighbours, Peter Antonenko, has written a fascinating book about his father Andrii. To be strictly correct, the book is Andrii’s memoir of his life, as recounted to Peter. Nobody’s Soldier tells the harrowing tale of Andrii’s early life, as an exemplar of the horrors that Stalin’s Russia brought against the people of Ukraine. These horrors started for him in his early teens, and continued through years of unimaginable struggle and hardship. That he emerged as such an apparently calm, decent and loving person is a testament to his resilience and strength.

As the online summary outlines,

Born in Ukraine in 1922, shortly before the Communist purge of the Kulaks, he and his family were forced from their farm land and transported to a labour camp in the Arctic Circle. Andrii escaped the camp at a tender age and what ensued was a tale of extraordinary resilience and survival.

Andrii bore witness to his father being arrested by the Communists and beaten mercilessly by political police, upon his refusal to relinquish his land. This injustice spurred Andrii into becoming adept at extricating himself from incarceration and capture by the Russians, Germans and the British on many occasions throughout his life.

Andrii was conscripted to the Red Army in 1941 immediately prior to the German invasion of Russia in World War II and was wounded in battle. Following his recovery, he was forced to join the German Army where he suffered before escaping and joining the Italian Partisans.

Constantly in fear and on the edge of starvation, Andrii survives freezing weather; being shot, beaten and attacked; a torpedo; and finally, tuberculosis. Hiding from covert and overt enemies was a priority as he travelled vast distances on foot. One journey taking six weeks to walk 1800 kilometres across Russia and Ukraine to be united with his family.

Through luck and deception, Andrii joined the Polish Division of the British Army to escape being repatriated by the Soviets and exterminated as part of their cleansing program. It was in Britain that Andrii met his wife and in 1959, emigrated to Australia with their two sons.

Nobody’s Soldier provides a glimpse into the geopolitical and social environment during one of the most poignant moments in world history, told through the lense of a strong willed, gentle man with an unquenchable love for his family and his country.

Yes, it’s all of this and more, including an extended period in Italy, where he clearly came to know and love the Italian people, always generous in their hospitality, despite their own deprivations.

As I look at what I’ve written, there’s a clear pattern of non-fiction here, especially with a focus on mid-20th century history and WW2. That isn’t all I read, but that’s another story.