In recent years we’ve been treated (if that’s the right word) to multimedia offerings that seemingly reveal the realities of World War I. Two specific examples are the much-lauded film 1917, and, more significantly, Peter Jackson’s magnificent They Shall Not Grow Old, amassed from archival footage from the Imperial War Museum. But what about the printed form? The book that resonated with me is Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That, which I’ve recently re-read after a couple of decades.

Goodbye to All That is Graves’ account of his early life and experiences as a young officer on the battlefields of France in 1915 and 1916, including time spent in the infamous trenches. It is gritty and disturbing, and certainly written with a strong air of authenticity. A highly personal account, it justifiably provides lengthy details Graves’ early life and schooling, including his time at the well-known English public school, Charterhouse, from which 698 pupils went to their deaths in the Great War.

Goodbye to All That is Graves’ account of his early life and experiences as a young officer on the battlefields of France in 1915 and 1916, including time spent in the infamous trenches. It is gritty and disturbing, and certainly written with a strong air of authenticity. A highly personal account, it justifiably provides lengthy details Graves’ early life and schooling, including his time at the well-known English public school, Charterhouse, from which 698 pupils went to their deaths in the Great War.

Although the book was written a decade or so after the war, some sections dealing with life in the trenches were copies of letters Graves had sent home. For example,

We are now in a nasty salient, a little to the south the brick-stacks, where casualties are always heavy. The company had seventeen casualties yesterday from bombs and grenades. The front trench averages thirty yards from the Germans. Today, at one part, which is only twenty yards away from an occupied German sap, I went along whistling ‘The Farmer’s Boy’, to keep up my spirits, when suddenly I saw a group bending over a man lying at the bottom of the trench. He was making a snoring noise mixed with animal groans. At my feet lay the cap he had worn, splashed with his brains. I had never seen human brains before; I somehow regarded them as a poetical figment. One can joke with a badly- wounded man and congratulate him on being out of it. One can disregard a dead man. But even a miner can’t make a joke that sounds like a joke over a man who takes three hours to die, after the top part of his head has been taken off by a bullet fired at twenty yards’ range.

Robert Graves ‘quite blindly’ joined the Royal Welch (yes Welch, not Welsh) Fusiliers, and overall was glad to have done so. His outline of the history, accomplishments and particular idiosynchaeies of the regiment is detailed and illuminating. “‘Welch’ referred us somehow to the archaic North Wales of Henry Tudor and Owen Glendower and Lord Herbert of Cherbury, the founder of the regiment; it dissociated us from the modern North Wales of chapels, Liberalism, the dairy and drapery business, slate mines, and the tourist trade.”

Robert Graves ‘quite blindly’ joined the Royal Welch (yes Welch, not Welsh) Fusiliers, and overall was glad to have done so. His outline of the history, accomplishments and particular idiosynchaeies of the regiment is detailed and illuminating. “‘Welch’ referred us somehow to the archaic North Wales of Henry Tudor and Owen Glendower and Lord Herbert of Cherbury, the founder of the regiment; it dissociated us from the modern North Wales of chapels, Liberalism, the dairy and drapery business, slate mines, and the tourist trade.”

Interspersed in the narrative are Graves’ encounters and friendships with a number of well-known historical and literary figures of the time, including the mountaineer George Mallory (best man at his first wedding), T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia), writer Thomas Hardy and poet Siegfried Sassoon. He met Sassoon while serving in France, and shortly after first encountering him writes:

At this time I was getting my first book of poems, Over the Brazier, ready for the press; I had one or two drafts in my pocket-book and showed them to Siegfried. He frowned and said that war should not be written about in such a realistic way. In return, he showed me some of his own poems. One of them began:

Return to greet me, colours that were my joy,

Not in the woeful crimson of men slain …

Siegfried had not yet been in the trenches. I told him, in my old-soldier manner, that he would soon change his style.

The following brief quotes provide illustrations of particular aspects of Graves’ war experience:

Ages of men in platoon: “The [official] ages for their ages are misleading. On enlistment, all over-age men had put themselves in the late thirties, and all under-age men had called themselves eighteen.” Of his forty men, at least fourteen were over forty, with one, when asked when he’d last fired a rifle, replied “In Egypt in 1882”. He was sixty-three. Five men were in reality boys. The youngest “was really only fifteen. He used to get into trouble for falling asleep on sentry duty, an offence punishable with death, but could not help it. I had seen him suddenly go to sleep, on his feet, while holding a sandbag open for another fellow to fill.” Both died later in the war.

Early experience of trenches: “We passed a group of men huddled over a brazier – small men, daubed with mud, talking quietly together in Welsh. They were wearing waterproof capes, for it had now started to rain, and cap-comforters, because the weather was cold for May. Although they could see we were officers, they did not jump to their feet and salute. … We overtook a fatigue-party struggling up the trench loaded with timber lengths and bundles of sandbags, cursing plaintively as they slipped into sump-holes or entangled their burdens in the telephone wire. Fatigue-parties were always encumbered by their rifles and equipment, which it was a crime ever to have out of reach. After squeezing past this party, we had to stand aside to let a stretcher-case pass. ‘Who’s the poor bastard, Dai?”, the guide asked the leading stretcher-bearer. ‘Sergeant Gallagher,’ Dai answered. ‘He thought he saw a Fritz in No Man’s Land near our wire, so the silly booger takes one of them new issue percussion bombs and shots it at ‘im. Silly booger aims too low, it hits the top of the parapet and bursts back. Deoul! man it breaks his silly f_ing jaw and blows a great lump from his sill f_ing face, whatever. Poor silly booger! Not worth sweating to get him back! He’s put paid to, whatever.’ The wounded man had a sandbag over his face. He died before they got him to the dressing-station.”

Early experience of trenches: “We passed a group of men huddled over a brazier – small men, daubed with mud, talking quietly together in Welsh. They were wearing waterproof capes, for it had now started to rain, and cap-comforters, because the weather was cold for May. Although they could see we were officers, they did not jump to their feet and salute. … We overtook a fatigue-party struggling up the trench loaded with timber lengths and bundles of sandbags, cursing plaintively as they slipped into sump-holes or entangled their burdens in the telephone wire. Fatigue-parties were always encumbered by their rifles and equipment, which it was a crime ever to have out of reach. After squeezing past this party, we had to stand aside to let a stretcher-case pass. ‘Who’s the poor bastard, Dai?”, the guide asked the leading stretcher-bearer. ‘Sergeant Gallagher,’ Dai answered. ‘He thought he saw a Fritz in No Man’s Land near our wire, so the silly booger takes one of them new issue percussion bombs and shots it at ‘im. Silly booger aims too low, it hits the top of the parapet and bursts back. Deoul! man it breaks his silly f_ing jaw and blows a great lump from his sill f_ing face, whatever. Poor silly booger! Not worth sweating to get him back! He’s put paid to, whatever.’ The wounded man had a sandbag over his face. He died before they got him to the dressing-station.”

Bombs and bullets: “… whereas we could usually hear a shell approaching, and take some sort of cover, the rifle-bullet gave no warning. So, though we learned not to duck a rifle-bullet because, once heard, it must have missed, it gave us a worse feeling of danger. Rifle-bullets in the open went hissing into the grass without much noise, but when we were in a trench, the bullets made a tremendous crack as they went over the hollow. Bullets often struck the barbed wire in front of the trenches, which sent them spinning with a head-over-heels motion – ping! rockety-ockety-ockety-ockety into the woods behind.”

“Our greatest trial was the German canister – a two gallon drum with a cylinder containing about two pounds of an explosive called ammonia that looked like salmon paste, smelled like marzipan, and, when it went off, sounded like the Day of Judgement. The hollow around the cylinder contained scrap metal, apparently collected by French villagers behind the German lines, rusty nails, fragments of British and French shells, spent bullets, and the screws, nuts and bolts that heavy lorries leave behind on the road. We dissected one unexploded canister, and found in it, among other things, the cog-wheels of a clock and half a set of false teeth. The canister could easily be heard approaching and looked harmless in the air, but its shock was as shattering as the very heaviest shell. It would blow in any but the very deepest dug-outs; and the false teeth, rusty nails, cog wheels and so on went flying all over the place. We could not agree how the Germans fired a weapon of that size. The problem remained unsolved until July 1, when the battalion attacked from these same trenches and discovered a wooden cannon buried in the earth and discharged with a time-fuse. The crew offered to surrender, but our men had sworn for months to get them.”

Suicide: “… I saw a man lying on his face in a machine-gun shelter. I stopped and said: ‘Stand-to, stand-to, there!’ I flashed my torch on him and saw that one of his feet was bare. The machine-gunner beside him said: ‘No good talking to him, sir.’ I asked: ‘What’s wrong? Why has he taken his boot and sock off?’ ‘Look for yourself, sir!’ I shook the sleeper by the arm and noticed suddenly the hole in the back of his head. He had taken off the boot and sock to pull the trigger of his rifle with one toe; the muzzle was in his mouth.’Why did he do it?’, I asked. ‘He went through the last push, sir, and that sent him a bit queer; on top of that he got bad news from Limerick about his girl and another chap.’ … Two Irish officers came up. ‘We’ve had several of these lately,’ one of them told me. Then he said to the other: ‘While I remember, Callaghan, don’t forget to write to his next-of-kin. Usual sort of letter; tell them he died a soldier’s death, anything you like. I’m not going to report it as a suicide.’

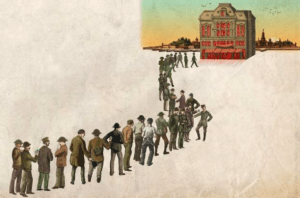

Brothels: “The Red Lamp, the army brothel, was around the corner in the Main Street. I had seen a queue of a hundred and fifty men waiting outside the door, each to have his short turn with one of the three women in the house. My servant, who had stood in the queue, told me that the charge was ten francs a man – about eight shillings at that time. Each woman served nearly a battalion of men every week for as long as she lasted. According to the assistant provost-marshal, three weeks was the usual limit: ‘after which she retired on her earnings, pale but proud.'”

Brothels: “The Red Lamp, the army brothel, was around the corner in the Main Street. I had seen a queue of a hundred and fifty men waiting outside the door, each to have his short turn with one of the three women in the house. My servant, who had stood in the queue, told me that the charge was ten francs a man – about eight shillings at that time. Each woman served nearly a battalion of men every week for as long as she lasted. According to the assistant provost-marshal, three weeks was the usual limit: ‘after which she retired on her earnings, pale but proud.'”

“There was a ‘Blue Lamp’ at Amiens, as at Abbeville, Le Havre, Rouen, and all the large towns behind the lines: the Blue Lamp reserved for officers, the Red Lamp for men.”

Risk: “… I had cannily worked it out like this. My best way of lasting through to the end of the war would be to get wounded. The best time to get wounded would be at night and in the open, with rifle fire more or less unaimed and my whole body exposed. Best, also, to get wounded when there was no rush on the dressing-station services, and while the back areas were not being heavily shelled. Best to get wounded, therefore, on a night patrol in a quiet sector. One could usually manage to crawl into a shell hole until help arrived. … Like everyone else, I had carefully worked out formula for taking risks. In principle, we would all take any risk, even the certainty of death, to save life or to maintain an important position. To take life we would run, say, a one-in-five risk, particularly if there was some wider object than merely reducing the enemy’s manpower; for instance, picking of a well-known sniper, or getting fire ascendancy in trenches where the lines came dangerously close.”

Snipers: “While sniping form a knoll in the support line, where we had a concealed loop-hole, I saw a German, perhaps seven hundred yards away, through my telescopic sights. He was taking a bath in the German third line. I disliked the idea of shooting a naked man, so I handed the rifle to the sergeant with me. ‘Here, take this. You’re a better shot than I am.’ He got him; but I had not stayed to watch.” … “The Germans had special regimental snipers, trained in camouflaging themselves. I saw one killed once at Cuinchy, who had been firing all day fro a shell-hole between the lines. He wore a sort of cape made of imitation grass, his face was painted green and brown, and his rifle was also green-fringed. A number of empty cartridges lay beside him, and his cp bore the special oak-leaf badge. few of our battalions attempted to get control the sniping situation. The Germans had the advantage of having many times more telescopic sights than we did, and bullet-proof steel loop-holes. Also a system by which snipers were kept for months in the same sector until they knew all the loop-holes and shallow places in our trenches, and the tracks that our ration parties used above-ground by night, and where our traverses occurred, and so on, better than most of us did ourselves. British snipers changed their trenches, with their battalions, every week or two, and never had time to study the German trench-geography. … It puzzled us that when a sniper had been spotted and killed, another sniper would often begin operations next day from the same position. The Germans probably underrate us, and regarded their loss as an accident.”

Snipers: “While sniping form a knoll in the support line, where we had a concealed loop-hole, I saw a German, perhaps seven hundred yards away, through my telescopic sights. He was taking a bath in the German third line. I disliked the idea of shooting a naked man, so I handed the rifle to the sergeant with me. ‘Here, take this. You’re a better shot than I am.’ He got him; but I had not stayed to watch.” … “The Germans had special regimental snipers, trained in camouflaging themselves. I saw one killed once at Cuinchy, who had been firing all day fro a shell-hole between the lines. He wore a sort of cape made of imitation grass, his face was painted green and brown, and his rifle was also green-fringed. A number of empty cartridges lay beside him, and his cp bore the special oak-leaf badge. few of our battalions attempted to get control the sniping situation. The Germans had the advantage of having many times more telescopic sights than we did, and bullet-proof steel loop-holes. Also a system by which snipers were kept for months in the same sector until they knew all the loop-holes and shallow places in our trenches, and the tracks that our ration parties used above-ground by night, and where our traverses occurred, and so on, better than most of us did ourselves. British snipers changed their trenches, with their battalions, every week or two, and never had time to study the German trench-geography. … It puzzled us that when a sniper had been spotted and killed, another sniper would often begin operations next day from the same position. The Germans probably underrate us, and regarded their loss as an accident.”

Rats: “They came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses, and multiplied exceedingly. While I stayed here with the Welsh, a new officer joined the company and, in token of welcome, was given a dug-out containing a spring bed. When he turned in that night, he heard a scuffling, shone his torch on the bed, and found two rats on his blanket tussling for the possession of a severed hand. This story circulated as a great joke.”

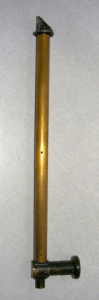

Periscope: “I now had a trench periscope, a little rod-shaped metal one, sent me from home. When I poked it up above the parapet, it offered only an inch-square target to the German snipers; yet a sniper at Cuinchy, in May, drilled it through, exactly central, at four hundred yards range. I sent it back as a souvenir; but my mother, practical as usual, returned it to the makers and made them change it for a new one.”

Periscope: “I now had a trench periscope, a little rod-shaped metal one, sent me from home. When I poked it up above the parapet, it offered only an inch-square target to the German snipers; yet a sniper at Cuinchy, in May, drilled it through, exactly central, at four hundred yards range. I sent it back as a souvenir; but my mother, practical as usual, returned it to the makers and made them change it for a new one.”

Gas warfare: In September 1915, Graves’ company received orders which included: ‘The attack will be preceded by forty minutes’ discharge of the accessory [gas], which will clear the path for a thousand yards, so that the two railway lines will be occupied without difficulty. Our advance will follow closely behind the accessory. … Owing to the strength of the accessory, men should be warned against remaining too long in captured trenches where the accessory is likely to collect, but to keep to the open and above all to push on. It is important that if smoke-helmets have to be pulled down they must be tucked in under the shirt.’ His captain commented: “It’s damnable. It’s not soldiering to use stuff like that, even though the Germans did start it. It’s dirty, and it’ll bring us bad luck. We’re sure to bungle it.” After a detailed outline of the shambolic lead-up to the attack, Graves explains: “All we heard back there in the sidings was a distant cheer, confused crackle of rifle fire, yells, heavy shelling on our front line, more shots and yells, and a continuous rattle of machine guns. … ‘What happened? What happened?’ I asked. ‘Bloody balls-up,’ was the most detailed answer I could get. Among the wounded were a number of men yellow-faced and choking, their buttons tarnished green – gas cases. … The company advanced with clatter of steel, … at half past four an R.E. captain commanding the gas-company in the front line phoned through to divisional headquarters: ‘Dead calm. Impossible discharge accessory.’  The answer he got was: ‘Accessory to be discharged at all costs.’ Thomas had not over-estimated the gas-company’s efficiency. The spanners for unscrewing the cocks of the cylinders proved, with two or three exceptions, to be misfits. The gas-men rushed about shouting for the loan of an adjustable spanner. They managed to discharge one or two cylinders; the gas went whistling out, formed a thick cloud a few yards off in No Man’s Land, and then gradually spread back into our trenches. The Germans, who had been expecting gas, immediately put on their gas-helmets: semi-rigid ones, better than ours. Bundles of oily cotton-waste were strewn along the German parapet and set alight as a barrier to the gas. Then their batteries opened our lines. The confusion in the front trench must have been horrible; direct hits broke several of the gas-cylinders, the trench filled with gas, the gas-company stampeded.” Then follows a detailed description of the carnage amid the confusion, with numerous pointless casualties. He continues: “We went up to the corpse-strewn front line. The captain of the gas-company, who was keeping his head and wore a special oxygen respirator, had by now turned off the gas-cocks. Vermorel-sprayers had cleared out most of the gas, but we were still warned to wear our masks. We climbed up and crouched on the fire-step, where the gas was not so thick – gas, being heavy, kept low. … Meanwhile, the intense bombardment that was to follow the forty minutes’ discharge of gas began. It concentrated on the German front trench and wire. A good many shells fell short, and we had further casualties from them. In No Man’s Land, the survivors of the Middlesex and of our ‘B’ and ‘C’ companies suffered heavily. … The Argyll and Sutherland had seven hundred casualties, including fourteen officers out of the sixteen who went over; the Middlesex, five hundred and fifty casualties, including eleven officers killed.” And then they had to clean up and do it again.

The answer he got was: ‘Accessory to be discharged at all costs.’ Thomas had not over-estimated the gas-company’s efficiency. The spanners for unscrewing the cocks of the cylinders proved, with two or three exceptions, to be misfits. The gas-men rushed about shouting for the loan of an adjustable spanner. They managed to discharge one or two cylinders; the gas went whistling out, formed a thick cloud a few yards off in No Man’s Land, and then gradually spread back into our trenches. The Germans, who had been expecting gas, immediately put on their gas-helmets: semi-rigid ones, better than ours. Bundles of oily cotton-waste were strewn along the German parapet and set alight as a barrier to the gas. Then their batteries opened our lines. The confusion in the front trench must have been horrible; direct hits broke several of the gas-cylinders, the trench filled with gas, the gas-company stampeded.” Then follows a detailed description of the carnage amid the confusion, with numerous pointless casualties. He continues: “We went up to the corpse-strewn front line. The captain of the gas-company, who was keeping his head and wore a special oxygen respirator, had by now turned off the gas-cocks. Vermorel-sprayers had cleared out most of the gas, but we were still warned to wear our masks. We climbed up and crouched on the fire-step, where the gas was not so thick – gas, being heavy, kept low. … Meanwhile, the intense bombardment that was to follow the forty minutes’ discharge of gas began. It concentrated on the German front trench and wire. A good many shells fell short, and we had further casualties from them. In No Man’s Land, the survivors of the Middlesex and of our ‘B’ and ‘C’ companies suffered heavily. … The Argyll and Sutherland had seven hundred casualties, including fourteen officers out of the sixteen who went over; the Middlesex, five hundred and fifty casualties, including eleven officers killed.” And then they had to clean up and do it again.

Attitude towards the French: “On the whole, troops serving in the Pas de Calais loathed the French and found it difficult to sympathize with their misfortunes. They had all the shortcomings of a border people. Also, we were shocked at the severity of French national accountancy; when we were told, for instance, that every British hospital train, the locomotive and carriages of which had been imported from England, had to pay a 200 pound fee for use of the rails on each journey they made from railhead to base. I wrote home about this time: ‘I find it very difficult to like the French here, except occasional members of the official class. Even when billeted in villages where no troops have been before, I have not met a single case of the hospitality that one meets among the peasants of other countries. It is worse than inhospitality here, for after all we are fighting for their dirty little lives. They suck enormous quantities of money out of us, too. … It was surprising that there were so few clashes between the British and the local French – who returned our loathing and were convinced that, when the war ended, we would stay and hold the Channel ports. We failed to realize that the peasants did not much care whether they were on the German or the British side of the line. They just had no use for foreign soldiers, and were not at all interested in the sacrifices that we might be making for ‘their dirty little lives.'”

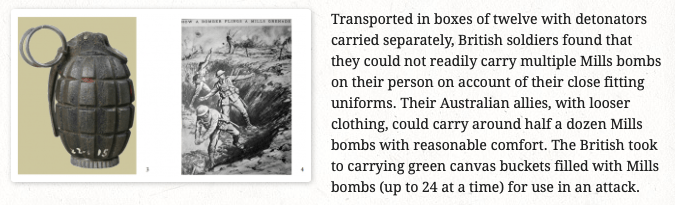

Atrocities: “For true atrocities, meaning personal rather than military violations of the code of war, few opportunities occurred – except in the interval between the surrender of prisoners and their arrival (or non-arrival) at headquarters. Advantage was only taken too often of this opportunity. Nearly every instructor in the mess could quote specific instances of prisoners having been murdered on the way back. The commonest motives were, it seems, revenge for the death of friends or relatives, jealousy of the prisoner’s trip to a comfortable prison camp in England, military enthusiasm, fear of being suddenly overpowered by the prisoners, or, more simply, impatience with the escorting job. … The troops with the worst reputation for acts of violence against prisoners were the Canadians (and later the Australians). … How far this reputation for atrocities was deserved, and how far it could be ascribed to the overseas habit of bragging and leg-pulling, we could not decide. At all events, most overseas men, and some British troops, made atrocities against prisoners a boast, not a confession. …  An Australian: ‘Well, the biggest lark I had was at Morlancourt, when we took it the first time. There were a lot of Jerries in a cellar, and I said to ’em: “Come out, you Camarades!” So out they came, a dozen of ’em, with their hands up. “Turn out your pockets,” I told ’em. They turned ’em out. Watches and gold and stuff, all dinkum. Then I said: “Now back to your cellar, you sons of bitches!” For I couldn’t be bothered with ’em. When they were all safely down I threw half a dozen Mills bombs in after ’em. I’d got the stuff all right, and we weren’t taking prisoners that day.”

An Australian: ‘Well, the biggest lark I had was at Morlancourt, when we took it the first time. There were a lot of Jerries in a cellar, and I said to ’em: “Come out, you Camarades!” So out they came, a dozen of ’em, with their hands up. “Turn out your pockets,” I told ’em. They turned ’em out. Watches and gold and stuff, all dinkum. Then I said: “Now back to your cellar, you sons of bitches!” For I couldn’t be bothered with ’em. When they were all safely down I threw half a dozen Mills bombs in after ’em. I’d got the stuff all right, and we weren’t taking prisoners that day.”

Being wounded: “… and eight-inch shell burst three paces behind me. I heard the explosion, and felt as though I had been punched rather hard between the shoulder-blades, but without any pain. … turning faint, I called to Moodie:’I’ve been hit.’ Then I fell. One piece of shell went through my left thigh, high up, near the groin; I must have been at the full stretch of my stride to escape emasculation. … But a piece of shell had also gone in two inches below the point of my right shoulder-blade and came out through my chest two inches above the right nipple. … Dr Dunn came up through the barrage with a stretcher-party, dressed my wound, and go the down to the old German dressing-station at the north end of Mametz Wood. I remember being put on the stretcher, and winking at the stretcher-bearer sergeant who had just said: ‘Old Gravy’s got it, all right!’ They laid my stretcher in a corner of the dressing station, where I remained unconscious for more than twenty-four hours. Late that night, Colonel Crawshay came back from High Wood and visited the dressing-station; he saw me lying in the corner, and they told him I was done for.”

The Colonel, back at headquarters, wrote letters of condolences to the families of the officers who’d been killed, including one to Robert Graves’ mother. He also made out a casualty list which included Graves’ ‘died of wounds’.

However, the next day, “clearing away the dead, they found me still breathing and put me on an ambulance for Heilly, the nearest field hospital. The pain of being jolted down the Happy Valley, with a shell hole at every three or four yards of the road, woke me up. I remember screaming. But back on the roads I became unconscious again.” Graves wounds were serious, especially the internal haemorrhaging into his right lung, but was taken back to England in a hospital ship and recovered some months later. The confusion of news of his death interspersed with notes of his survival naturally caused much consternation in his family, finally reaching profound relief when his survival was assured.

A cutting from The Times sums it up: ‘Captain Robert Graves, Royal Welch Fusiliers, officially reported died of wounds, wishes to inform his friends that he is recovering from his wounds at Queen Alexandra’s Hospital, Highgate, N.’

It was not all celebration and good times: “England looked strange to us returned soldiers.We could not understand the war-madness that ran wild everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet. The civilians talked a foreign language; and it was newspaper language. I found serious conversation with my parents all but impossible.”

For a while Graves retreated to poetry with Siegfried Sassoon, but both when recovered spent further time in the army, even retiring to France, though Graves stint was short-lived due to continuing health issues. His final efforts in the war were associated with training of new recruits.

The final chapters of Goodbye to All That concern the next decade of Graves’ life, mostly about his first marriage and domestic life, along with his departure from England and eventual settling in Majorca, where he wrote the book in 1929 at the age of thirty three.

The book landed ‘like a Zeppelin bomb’, as Sassoon reacted, and not at all favourably. There was considerable disquiet and unhappiness with Graves’ account, and my re-reading of it prompted me to investigate further. With respect to Sassoon, it seems that much of his angst had to do with Graves’ perspective on their relationship and publishing snippets of his poetry without permission. Goodbye to All That does go into Sassoon’s wartime exploits in some detail and highly positively, though does include Graves’ interpretations of his beliefs and reactions to war, along with his anti-war crusade.

The book landed ‘like a Zeppelin bomb’, as Sassoon reacted, and not at all favourably. There was considerable disquiet and unhappiness with Graves’ account, and my re-reading of it prompted me to investigate further. With respect to Sassoon, it seems that much of his angst had to do with Graves’ perspective on their relationship and publishing snippets of his poetry without permission. Goodbye to All That does go into Sassoon’s wartime exploits in some detail and highly positively, though does include Graves’ interpretations of his beliefs and reactions to war, along with his anti-war crusade.

Robert Graves’ father, Alfred, was so incensed by the book that a year after its publication he published his own autobiography, To Return to All That, attempting to balance some of what he perceived as Robert’s erroneous opinions of the family and recollections of war. I was curious whether Alfred was able to cast doubt on the veracity of Robert’s wartime reminiscences, so focussed on the second last chapter, ‘Robert Graves’. It makes for curious reading, as the first section attempts to clear up details of his motivations in choosing schools for Robert and defence of his reactions to Robert’s behaviour. With respect to the war, Alfred quotes extensively from letters which Robert wrote during this time in France, which were published in the Spectator in 1915.

Yes, the Spectator letters are written in a different vein than the later autobiography, but this is perfectly understandable, given the circumstances and perceived readership. Nevertheless, the ‘facts’ of the two accounts do not differ substantially, as can be seen by comparing this quote from a Spectator letter with the account in the third paragraph above.

Yes, the Spectator letters are written in a different vein than the later autobiography, but this is perfectly understandable, given the circumstances and perceived readership. Nevertheless, the ‘facts’ of the two accounts do not differ substantially, as can be seen by comparing this quote from a Spectator letter with the account in the third paragraph above.

So I’m not quite sure why Alfred quoted so extensively. Perhaps it was to show that Robert displayed a seemingly different attitude to war experience at the time of the conflagration, becoming bitter and resentful as time passed. Alfred also provides a detailed account of the mixup with respect to Robert’s death, which in no way detracts from the latter’s account.

Towards the end of the chapter, Alfred claims that “Goodbye to All That calls for many more corrections than I can here enumerate, having been written largely from memory, sometimes from hearsay, and often long after the events described.” He then goes on about family history and somewhat petulantly, claims that “He gives me no credit for the interest I always felt and showed in his poetry.” So overall it seems that this critique is mostly about family squabbles and misunderstandings.

Which takes us back to the fundamental question of whether Goodbye to All That provides us with a genuinely realistic account of the grim realities of the First World War. My answer is a firm yes.

PS I haven’t read it yet, but if you want more detail on this topic, get hold of Jean Moorcroft Wilson’s apparently excellent Robert Graves: From Great War Poet to Goodbye to All That. As a reviewer tantalisingly offers: “The real strength of this biography, however, lies in the care and vigour with which it animates the conflicting strands of Graves’s personality. To encounter him in these pages is to feel something of the relentlessly explosive energy with which he lived the first half of his life. Wilson lands him like a Zeppelin bomb.”