If you’ve worked in a university, you’ll be familiar with the tortuous machinations that inevitably erupt during internal elections. Examples are not as common as they once were (a specific instance being the installation of Deans, who are usually now appointed rather than elected), but they still exist, especially in more traditional institutions.

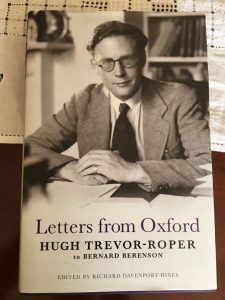

It’s with this in mind that I’ve just come across a most wondrous piece of writing on the thorny process of university elections. It’s in a book of letters by Hugh Trevor-Roper, the Oxford historian, to Bernard Berenson, a famous art critic. I’ve previously written a couple of posts about Trevor-Roper (‘Of Oxford, books and a theory of stupidity‘ and ‘The joy of a new book‘), and love his writing. The letter was written on July 6,1951 from Christ Church to Berenson at I Tatti (his marvellous villa near Florence – now the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies), and here is the relevant section (pp. 67-71):

It’s with this in mind that I’ve just come across a most wondrous piece of writing on the thorny process of university elections. It’s in a book of letters by Hugh Trevor-Roper, the Oxford historian, to Bernard Berenson, a famous art critic. I’ve previously written a couple of posts about Trevor-Roper (‘Of Oxford, books and a theory of stupidity‘ and ‘The joy of a new book‘), and love his writing. The letter was written on July 6,1951 from Christ Church to Berenson at I Tatti (his marvellous villa near Florence – now the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies), and here is the relevant section (pp. 67-71):

You must understand that there is in this university, as in all institutions (see the Bible, passim) a Party of Light (to which the writer belongs) and a Party of Darkness (consisting of those who hold different views). Our party of Light regards a University as a place of Learning and Pleasure, to be controlled by us; their party of Darkness regards it as a place of administrative efficiency and Dullness, to be controlled by them. These two parties are nearly always locked in apparently insoluble deadlock; which however is ultimately solved by the existence, at a far lower level, of a third party, conveniently described as the Jellies, or party of compromise. Whereas the Parties of Light and Darkness are distinguished by the enlightenment or blackness of their views, the Jellies – or perhaps I should say Jellyfish – are distinguished by their complete absence of any views. They float now this way, now that, as the tide ebbs or flows, sucked helplessly into the wake of ships passing now this way now that, sometimes stranded on the beach by the advancing tide, and left there to dissolve in the sun, sometimes carried by the receding tide, quavering, into the strange and terrifying currents of the uncomprehended Ocean. In spite of their general helplessness the Jellies have, however, two important qualities: first, though sometimes submerged, they never sink; secondly, though unable to control the direction of their movements, some of them can, if touched, sting. In periods of violent storm (naturalists observe) these Jellies appear in large numbers around our otherwise placid academic coasts; and the result of their intervention in our elections (I must now return from metaphor to the world of plain fact) is almost always the same: a compromise candidate is discovered who, in the exhaustion of both parties, is found acceptable by all. This compromise candidate always has certain important negative qualities whereby he secures this general assent. First, he appeals to the Party of Light by being thoroughly inefficient at administration; secondly he appeals to the Party of Darkness by showing no interest in either Learning or Pleasure. Thus, although nobody positively wants him, each party prefers him to the candidate of the other, and he is elected. This, in brief, is the analysis of all Oxford Elections. I now return to the two particular elections which have interrupted all work for the last two months: the election of a Warden of All Souls and the election of a Professor of History.

Of course the late Warden of All Souls had hardly been buried, and black hatchment had hardly been hung out, like a somewhat tipsy pub-sign, over the college gate, before the preparations and speculations about the succession had begun. There are in All Souls 51 voting Fellows, and a candidate, to be elected Warden, must obtain at least 26 votes at the formal meeting; but before this formal meeting there are preliminary meetings at which those candidates who are thought to be worth running are selected by a straw vote. Our candidate was, of course, Isaiah Berlin. Theirs was, of course, a professional administrator. At the first straw vote they obtained a majority for their candidate, Sir Edward Bridges, head of the civil service, Isaiah being second; but Bridges declined the offer, and from this moment the battle can be said to have begun.

The most determined advocate of Darkness in All Souls – A.L. Rowse – happened, at this crucial juncture, to be in California, and ever since airplanes were invented he has loudly declared that his neuroses would never allow him to travel in such a vessel; but when the fate of Darkness in Oxford hung thus precariously in the balance, he at once disinterestedly jettisoned his long and carefully sustained neuroses and appeared within a few days in the surprised cloisters of All Souls. For a week every alcove hummed; then, at the next meeting of the Fellows, when a new straw vote was taken in consequence of the retreat of Bridges, 26 Fellows, with apparent unanimity, supported the proposal of Rowse of a hitherto quite unknown figure: Sir Eric Beckett. Such support, if repeated at the official meeting, would infallibly bring Beckett in. The question which everybody naturally asked (including some of those who had already voted for him) was, Who is Sir Eric Beckett?

Deep research has been devoted to this problem. So far the only clear facts which have emerged are that Sir Eric Beckett is (thanks to an airplane crash which killed his superior) legal adviser to the Foreign Office; that he was once struck in the face by Douglas Jay who, though himself a well-behaved Wykehamist, was outraged beyond endurance by his pro-Franco views, and that he has twice been in a lunatic asylum.

Conceive, if you can, the crescendo of buzzing in the alcoves, the feverish motion from staircase to staircase in these normally somnolent quadrangles, the sudden attentiveness towards young voters of hitherto aloof elderly peers, the carefully timed indiscretions and skilfully calculated chance meetings by which, in the next fortnight, each party sought desperately to detach from the other its floating voters; and having conceived it, transport yourself in imagination to the official meeting at which whoever obtained 26 votes would thereby become Warden of the College. The first proposal was made by Rowse who, as sub-warden, controlled the machinery of debate. He proposed Sir Eric Beckett; and thereupon the carefully oiled mechanism of election began those calculated revolutions which would slide the candidate effortlessly into place. Began – but did not complete them. Suddenly strange creaks issued from parts of the equipment, as if saboteurs had secretly inserted sand in some essential aperture. The great engine groaned suddenly to a standstill, and certain small but important cogs, rods or pistons had not moved – with disastrous consequences: the candidate was not in place. In spite of his earlier absolute majority, he had now only got 23 votes; and 23 votes are not enough.

At once the Party of Light advanced to try their hand at the machine. Their candidate in turn was placed on the springboard: Isaiah Berlin; and the Party foremen wound enthusiastically with the recalcitrant handles. But once again certain essential springs failed to respond, and the candidate could not be carried forward into the Warden’s lodgings. He had only obtained 21 votes, and 21 votes are not enough either.

And now began a famous scene which will long be remembered in Oxford history and quoted in the manuals of our constitutional procedure. Each party in despair began to put up candidate after candidate in the hope of breaking the deadlock, and every advocate of Light, and every advocate of Darkness, in turn submitted to the test in the hope of detaching either three votes in one direction or five in the other in order to achieve a majority. Scenes of indescribable confusion followed. Twice did Isaiah withdraw his candidature amid applause from his adversaries; twice was he dragged back by his supporters. Now one hand, now another, grasped the handle of the obstinate machine, but failed to turn it. The issue was always the same. Whoever stood against Isaiah infallibly obtained 23 votes – the voting strength of embattled Darkness; whoever stood against Beckett as infallibly obtained 21 votes – the voting strength of mobilised Light. There was total deadlock. What was to be done?

At this point the watchers on the academic cliffs began to espy, out at sea, the familiar phenomenon of the storm: great shoals of Jellies drifting slowly towards the shore; and within the conclave, by a natural consequence of this news, the cry for a compromise candidate began to be heard. The question was, who could that compromise candidate be? You will have observed that the full toll of voters was 51, but also that the united voting strength of the two parties amounts only to 44; and whereas we can account for one of the omissions by the fact that the candidate of the moment was always out of the room at the time of the voting, and for a second by the fact that one voter – Professor Wheare – overcome by the strain of the conclave, had been carried out on a stretcher, there are still other abstainers to be accounted for. Naturally it was among these abstainers that a compromise candidate would be sought. Who among them was the most appropriate candidate?

Sir Hubert Henderson, Drummond Professor of Political Economy, is a respectable elderly gentleman who is generally known in Oxford for one reason only: in 1949 he made, before the largest meeting of Convocation ever remembered in Oxford, the most boring speech that has ever been heard in that assembly. Had there been any votes to lose on that occasion it is universally agreed that Henderson’s speech would indubitably have lost them all. (In fact his speech made no difference at all: everyone came to that meeting with his mind so firmly made up that no oratory, however plausible, could have altered it: for we were voting an increase in our own salaries). When the first straw vote for the Wardenship of All Souls was taken, Sir Hubert Henderson had only obtained one vote; and it was perhaps this fact which (by rendering the whole issue academic to him) had cause him to sleep, and thereby to abstain, throughout the long struggle of parties. At all events, when the deadlock within the college walls was complete, and the swish of Jellies in the tide had suddenly become audible, the double fact that nobody seemed to want Sir Hubert Henderson and that Sir Hubert Henderson did not seem to want anyone, naturally made him the man of the hour. And thus it was that suddenly, at the crucial moment, when Sir Hubert Henderson was placed in the machine, the handle at last turned effortlessly in its socket, the wheels revolved, the rods and cams, ratchets and pinions all slid with lubricated ease on their intended courses, and the candidate was at last, by 36 votes, carried effortlessly forward into the Warden’s lodgings at All Souls.It only remains to add that Sir Hubert Henderson, overcome by the excitement of election, has retired to hospital with a heart attack; so a spare hatchment has been commissioned and discreet preparations are already, but I hope wrongly, being made for a resumption of the struggle.

From the sublime to the ridiculous!

Isn’t there a proverb about this?

“The more things change…”