In an earlier post on reviewing, I noted the claimed contribution to the death of Keats by the savage review of his poetry by one John Wilson Croker. It appeared in the Quarterly Review, of which I now own a copy of Volume LXIV (1839), a most welcome and expected (as I chose it in an antiques shop in Tetsworth) Christmas present.

It’s not the volume with Croker’s review (that was in 1817), but it does have a review of Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens, and fascinating reading it makes indeed! It’s long, complex, sophisticated and sneeringly superior, not surprising for what was essentially a conservative publication. I found it fascinating, not just because it revealed how far the craft of reviewing had developed, but also showed just how political it had become. Though not specifically named the reviewer is most probably the editor, John Gibson Lockhart.

Much of it makes for challenging reading, as it is replete with references to current affairs (persons and events) unfamiliar to most of us (well, me anyway). To illustrate, here’s the beginning:

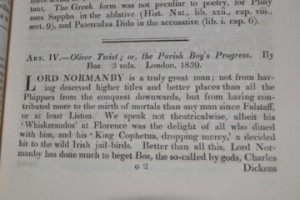

Here’s said text, starting on page 83. Notice how each page finishes with the addition of the first word from the next page – nice idea!

“LORD NORMANBY is a truly great man; not from having deserved higher titles and better places than all the Phippses from the conquest downwards, but from having contributed more to the mirth of mortals than any man since Falstaff, or at least Liston. We speak not theatricalwise, albeit his ‘Whiskerados’ at Florence was the delight of all who dined with him, and his ‘King Cophetua, dropping mercy’, a decided hit to the Irish jail-birds. Better than all this, Lord Normanby has done much to beget Boz, the so-called by gods, Charles Dickens by men. Boz eclipses in public estimation those imps of fame, Spring Rice and jumping Jim Crow Rice.”

Whew! Well, I started to try to ‘deconstruct’ what it all meant, but didn’t get far. My searches revealed, for example:

Lord Normanby: little doubt that this is Constantine Henry Phipps (hence the further reference to the Phippses), 1st Marquess of Normanby. He was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1835 to 1839, providing a link to the reference in the second sentence to ‘Irish jail-birds’. Apparently a well-known writer, he was responsible for The English in Italy (1825); in the same year he made his appearance as a novelist with Matilda, and in 1828 he produced another novel, Yes and No. And an examination of his parliamentary history produced this relevant pithy quote: ‘the Normanbys are at Florence trying to get up a theatre’, in which venture ‘they will I hear succeed but have more actors than audience’.

Falstaff: a character in three of Shakespeare’s plays; a comic figure, Falstaff appears as a ‘fat, vain, boastful and cowardly knight’.

Liston: this one has me beaten, though my search did lead me to Robert Liston, a surgeon of the time, famous for the speed with which he could amputate patient’s limbs (and bits of any assistant who stood too close).

Whiskerados and King Cophetua: also too much for me, though the latter’s origin is in a medieval story, and Shakespeare mentions him in Henry IV.

Boz: did you know that Boz was a pseudonym of Charles Dickens? He used it for ‘lighter’ pieces so as not to damage the credibility of his more serious publications. Oliver Twist was originally published under the authorship of Boz.

Spring Rice and jumping Jim Crow Rice: this is reference to Thomas Dartmouth Rice, a predecessor of the white entertainers who blackened their faces in the minstrel shows, the ‘Jim Crow’ (later a pejorative term) referring to a particular song and dance act he performed.

And on it goes. Some is more readily digestible, especially the bits that are critical (both obliquely and directly) of Oliver Twist, and here’s a sample:

“It is perfectly natural that Oliver Twist … should be the joy of the ten-pounders.: it is another affair why the ten thousand and ten thousand a-year men should join this universal suffrage.”

“… Turpin and Macheath yield in consequence to the ‘artful Dodger’ – skill, address, and slang are the order of this age – ‘cedunt arma togae’ [what weapons yield to the toga]. These accomplishments are become a second nature and language to a vast number of her Majesty’s lower orders, whose strange habits excite a curiosity in the higher, their antipodes. Life in London, as revealed in the pages of Boz, opens a new world to thousands bred and born in the same city, whose palaces overshadow their cellars – for the one half of mankind lives without knowing how the other half dies: in fact, the regions about Saffron Hill [the squalid suburb where Fagin lived] are less known to our great world than the Oxford Tracts; the inhabitants are still less; they are human, to all appearance, as are the Esquimaux or the Russians, and probably (though the Zoological Society will not vouch for it) endowed with souls; but, whether souled or not souled, they are too far beneath the higher classes to endanger any loss of caste or contamination in the inquiry.”

“The works of Boz come out in numbers, suited to this age of division of labour, cheap and not too long – double merits: there is just enough to make us rise from the feast, as all doctors of divinity and medicine do from dinner, with an appetite for more: in fact, Boz is the only work which the superficial acres of type called newspapers leave the human race time to peruse. His popularity is unbounded – not that that of itself is a test of either honesty or talent …”

Ouch! Even if some of the references escape us, the intent is clear, and it’s not particularly positive. The reviewer does adopt a more complimentary tone briefly, though, when he writes:

“… the strength of Boz consists in his originality, in his observation of character, his humour – on which he never dwells. … Boz never ridicules the poor, the humble, the ill-used; he spares to real sorrow ‘the bitterest insult of a scornful jest’; his sympathies are on the right side and carry his readers with him. … He tells a tale of real crushing misery in plain, and therefore most effective, language; he never then indulges in false sentimentality, or mawkish, far-fetched verbiage.”

But the review then turns virulent again, as we learn that:

“Boz fails whever he attempts to write for effect; his descriptions of rural felicity and country scenery, of which he clearly knows much less than of London, where he is quite at home and wide awake, are, except when comical, over-laboured and out of nature. His ‘gentle and genteel folks’ are unendurable; they are devoid of the grace, repose, and ease of good society; a something between Cheltenham and New York.”

“Boz is regius professor of slang. … This is the great objection which we feel towards Oliver Twist. … We object to the familiarising our ingenuous youth with ‘slang’; it is base in travestie of better things. … The jests and jeers of the ‘slangers’ leave a sting behind them. They corrupt pure taste and pervert morality, for vice loses shame when treated as a fool-born joke, and those who are not ashamed to talk of a thing will not be ashamed to put it into practice.”

” Oliver Twist … is directed against the poor-law and work-house system, and in our opinion with much unfairness. The abuses which he ridicules are not only exaggerated, but in nineteen cases out of twenty do not at all exist.”

“The plot, if it not be an abuse of terms to use such an expression, turns on the early misfortunes, persecutions, and final prosperity of Mr. Oliver Twist.”

“The whole tale rivals in improbabilities those stories in which the hero at his birth is cursed by a wicked fairy and protected by a good one; but Oliver himself, to whom all these improbabilities happen, is the most improbable of all.”

And there’s much more – 19 pages of it. Even the summary of the plot is presented to accentuate incredulity. It’s dense, sophisticated and sharp – even if you don’t agree with it (and it raises some salient points), you have to admire it. If it hasn’t been done already, it would make a marvellous project or minor thesis for a postgraduate student in literature.

As for the book itself, Volume LXIV of the Quarterly Review has a lot else to savour. With my interest in maths, I quickly honed in on ‘An Essay on Probabilities, and on their Application to Life Contingencies and Insurance Offices’, by Augustus de Morgan. The name was familiar to me from his famous law/theorem (a logic theorem now indispensable to digital electronics), and it also reminded me that I once considered trying out for actuarial studies.

There’s also a series of travellers’ tales, foreign office correspondence, an article on post office reform and (I kid you not) ‘Reports of the Society for the Suppression of Mendicity’ (not to be confused with ‘mendacity’).

I shall read on.